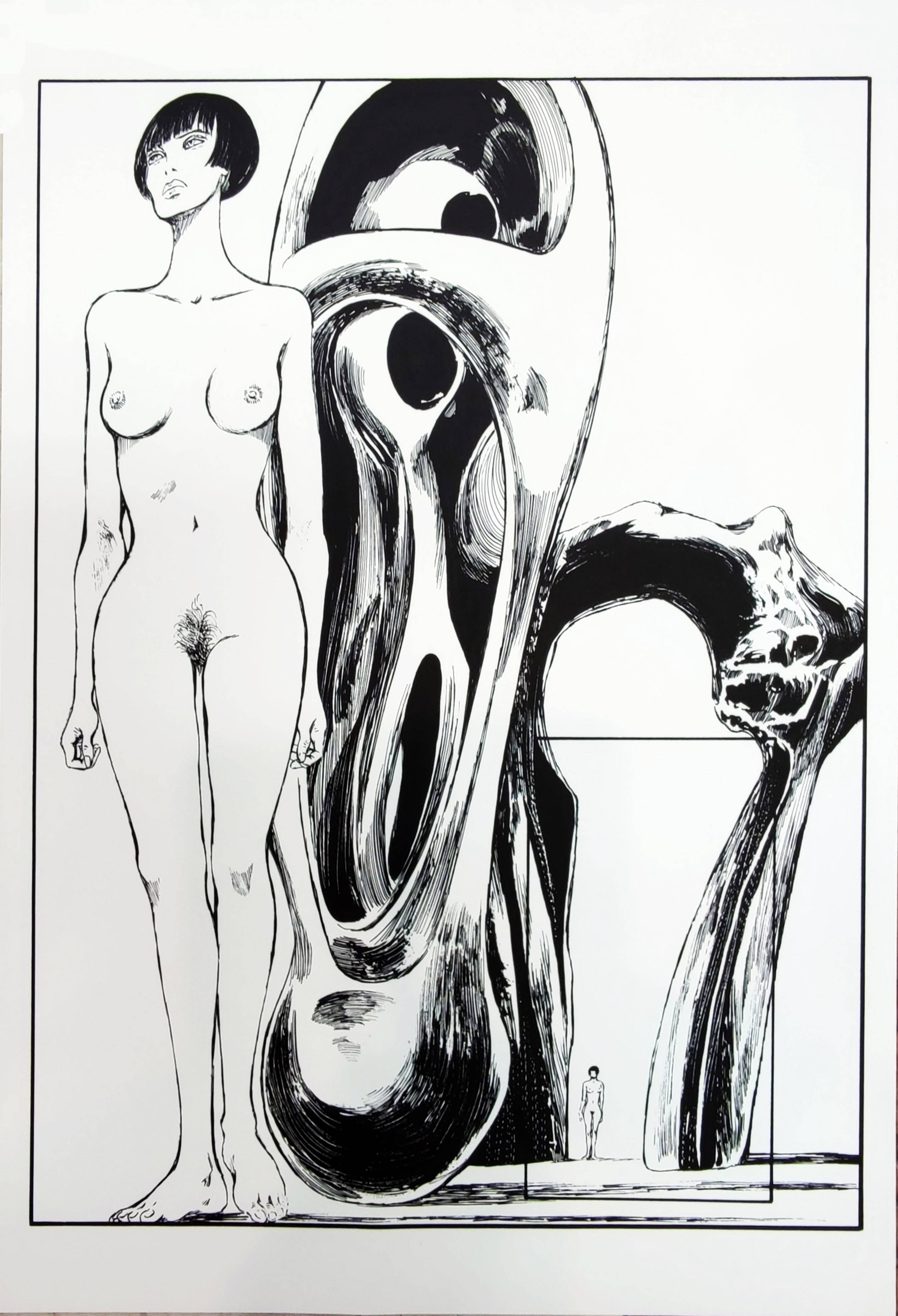

I think a lot of people see Crepax art and write it off as naked girls and bondage and don't give it the attention it deserves. There are naked girls and there are sadomasochistic themes through out the work but that is only a small part of it. The Valentina story revolves around the main character who lives in both a dreamlike world and the real world at the same time. The art, story telling and layouts are both abstract and cinematographic at the same time. What I appreciate most about Crepax are the layouts. Although this page is interesting from that perspective, it is his use of small and large panels that you see on other Crepax pages that is most innovative. It is the same thing I like about Chris Ware's work and when I met Chris at the Billy Ireland Museum last year I asked him if Crepax was an influence and he readily admitted that he was a big influence and one that he has not credited enough. Another aspect of Crepax's work is the use of themes and styles that show an appreciation of fine art and styles. I think the first panel is very much in a surrealistic style reminiscent of Tanguy or Dali only more kinetic and volatile like Munch. The uneven lower border and off kilter horizontal orientation of the scene adds to the sense of imbalance and chaos inducing a bit of vertigo. The direction of movement and hurricane winds in the panel is self evident within this ever widening panel give a sense of openness or void to whatever is in front of this scene. The bottom tier has an ever decreasing height and abstraction bringing us from the Dali nightmare gradually back to the real world. The one frame using photo negativity is interesting and masterfully rendered in inks and is not a reversed stat. The crescendo, decrescendo tempo to the chaos and noise of the page is very powerful, emotional storytelling and reflects the kind of genius Crepax had in his construction and design of a page. Valentina's trademark camera is evident in almost every panel. I am still reading through the series as it is translated into English. They are not easy reads as there are complex themes and the abstraction is open to interpretation. This particular page has not shown up in my reading (nor has my other page) and so I don't have a complete context for it. I also hope to explore the meaning of the camera motif in Valentina, is it a secret power, a weapon, an extension of her, a metaphor...

SHRDSH!!! Deliriums and Desires…

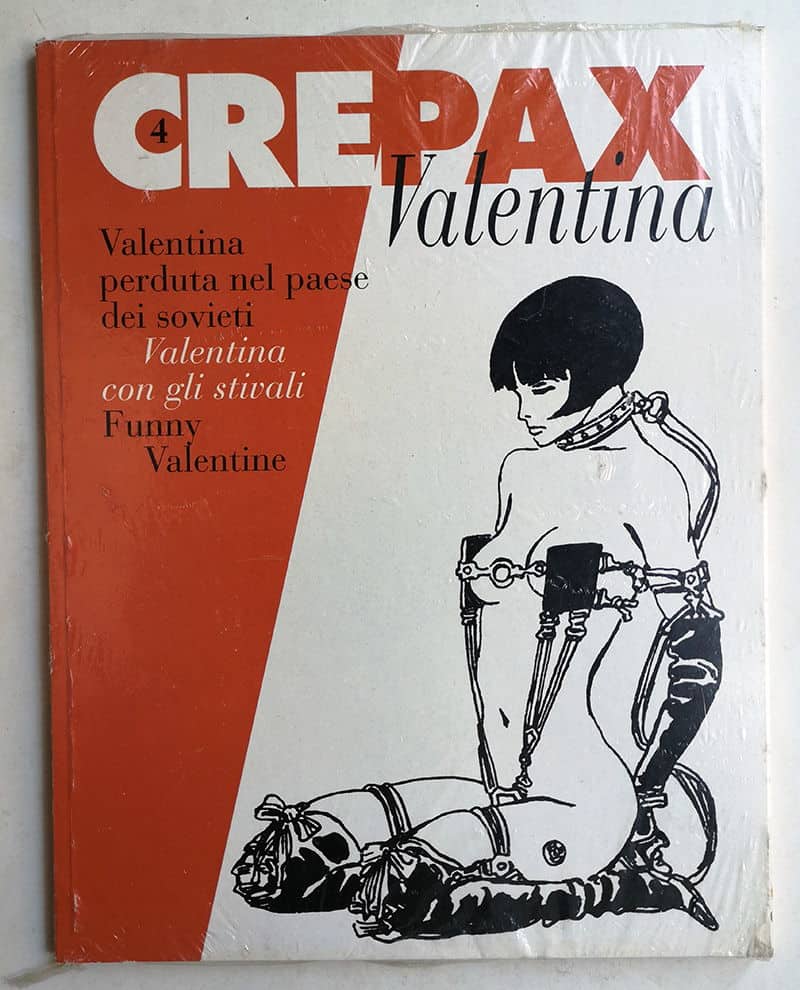

By Guido Crepax. In Volume 5, Valentina's rich fantasy life goes Hollywood, where she meets her inspiration, Louise Brookes, Bonnie and Clyde make an appearance, and Crepax pays homage to classic silent films. Volume 6 chronicles the adventurous Valentina's love affairs and features two of Crepax's lauded graphic adaptations: 'Venus in Furs' and 'The Memoirs of Casanova.' Portrait Valentina Crepax portrai,drawing 42 x 55 cm, ink and pencil technique (Ink and pencil) ArtISlifeArte. 5 out of 5 stars (2) $ 82.44.

by Stefan Prince,

an article written in the spring of 2000 and

published in Skin Two magazine #33

Crepax Valentina Orologio

bande dessinée or …”dessin qui bande”? (Roland Barthes)

Once upon a time in a North London book shop, long before its management became politically correct about its stock, Story of O by Italian comic strip wizard Guido Crepax could for a short while be purchased as a classy hardcover coffee table edition in French from publisher Jean Jacques-Pauvert.

Lucky were the keen-eyed of the day for, alas poor Crepax, with the banning of the film by the UK censors such luxuries were denied the would-be fetishist who was then forced to endure the lean years in which Crepax’s comic strip Story of O and other graphic novels such as Venus In Furs surfaced only occasionally in Soho book shops in rather less than classy US imports. Indeed the Grove Press paperback of Story of O had a total of 34 pages missing from the original, due seemingly to economic rather than moral censorship.

But now the lean years are over. Would-be-Crepax fans can at last pore over the full-monty of this unique “Raphael of Comics” thanks to the Evergreen imprint of publishers Taschen who have delivered two deluxe hardback editions in English comprising Venus in Furs/ Bianca/ Emmanuelle, and Justine/Story of O

Will the waiting be found worthwhile? For the Crepax fan yes, but for the general reader perhaps not. Comics have moved on at a pace and though Crepax’s line will still startle and impress his style harks back to his own ground-breaking period in which during the late sixties in France Jean Claude Forest unleashed Barbarella (1964) into pop culture and in Italy Guido Crepax set about completely restructuring the comic strip per se with the help of his very own ‘damsel in distress’ – Valentina.

Valentina will be seen to have been Crepax’s greatest contribution to cartoon literature and though conspicuous by her absence Valentina casts a shadow over both Taschen volumes, for the trappings of bondage and pure fantasy, half oneiric and half hallucinatory to be found throughout these later graphic novels, were unmistakably there already in early Valentina.

Valentina, the sophisticated Milanese photographer pursued relentlessly by sadistic Nazis, astronauts, 17th-century pirates, and leather-booted Czarist Cossacks, made her first appearance in the spring of 1965 appearing in the second issue of Linus, an Italian magazine devoted to comic-strip art to which friends asked Crepax to contribute. Crepax was thirty-two when he created Valentina, a late-comer perhaps, but certainly by then an experienced draughtsman. At twenty-five, he had graduated from the University of Milan with a degree in Architecture. Publicity work followed for companies such as Shell, Dunlop, Terital, and Fujica, then for several years Crepax supported himself by illustrating book covers and record sleeves, particularly for jazz recordings, and by contributing illustrations to magazines such as the medical journal Tempo Medico.

It was Valentina which proved for Crepax the potentiality of cartoon literature or ‘fumetti’, an art form he had previously attempted when as a young evacuee during World War Two in Venice he had read and loved the American cartoon strips Mandrake and Flash Gordon. “My first cartoon,” he recalls, “I did when I was twelve and it was called The Invisible Man, and it obviously followed very closely the film of the same name. I put everything together on my own, the screenplay as it were, the writing and the drawings…” Twenty years later Crepax set about creating his cartoon strip for Linus with the same attention to planning, storyline, lettering, and framing, inventing his own male superhero Neutron, “with the magnetic eyes of Mandrake and the physical build of the traditional Man In the Mask.” Gradually Neutron disappeared from the story. It was almost by chance and without premeditation that the true protagonist would prove to be Valentina, “the incarnation of Louise Brooks, the masochistic dreamer, the all-powerful photographer, the most beautiful androgyne with the most beautiful backside in the world”.

In a series of extravagant and often surreal adventures, Valentina would soon know the rages of bisexuality, autoerotic ecstasy, super-sensual abandon, and the sadomasochistic delirium. Her body given up without inhibition, fragmented on the page and scrutinized in minute detail in a style of syncopated editing which reminded critics of the French films of the sixties, the nouvelle vague, – Valentina would now scandalize many readers in Italy and abroad and be the inspiration for a series of similar sexy and captivating heroines who would keep Crepax busy at his drawing board for years to come.

Acknowledging the daring nature of his comics Crepax maintains his adult audience must be capable of seizing the ambiguities behind appearances, distinguishing the true fantasies from stark reality. “So if I have drawn whips, chains, bonds of every kind,” he says, “even if I have reproduced in my pictures the most audacious bold erotic perversions, I, in fact, hate violence and lack of respect towards oneself and to others, and all forms of excess. The extraordinary things that my poor young girls in love undergo – Valentina, and Bianca, Anita and Justine, Emmanuelle and Madame O – have nothing to do with the treatises on sexual psychopathology of Richard von Krafft-Ebing: they are only visionary exercises, imaginary madness transferred onto paper, deliriums, desires ruled by a purely cerebral mechanism… what interests me more than anything else is that the game never becomes obscene, that it is never trapped by vulgarity. Have a look at them, the girls on display… however they might be bound, frustrated, constrained, imprisoned, compressed or struck… there is never one single drop of blood. The blow on their skins in the end never leaves more of a mark than a firm embrace.”

The erotic intrigues and embraces which torment Valentina are of course by necessity, almost always nothing more than dreams, oneiric projections, surreal adventures beyond the real. Sometimes her son Matia’s comic books are a starting point for a daydream adventure. In one tale Crepax pays homage to his mentors by portraying Valentina in the style of Hugo Pratt, Milton Caniff, Alex Raymond, Stan Lee, and even John Willie, and introduces the comic book heroes of his childhood, Dick Tracy, Tarzan, Prince Valiant and Mandrake, into the storyline.

Time and again Crepax reinvents the layout of his page and in story-board fashion, the pictures tell the story almost to the exclusion of traditional balloon-enclosed dialogue. In the Valentina story, Magic Lantern dialogue is in fact dispensed with altogether.

It could be said that Valentina, described by Graziano Frediani as “the allegory of a need, a mirror in fragments, the mark left from a laceration…” has in Crepax’s Story of O become Madam O, the plaything of the valets and members of the Roissy mansion, of her lover René who takes her there, and of Sir Stephen who claims ownership by having O branded with his initials. The story unfolds like an adult fairy tale, familiar territory for Crepax. With consummate skill, he takes every opportunity presented by this sadomasochistic literary classic to busy his pages with all manner of menace, stylized violence, eroticism, and sex. Whips, masks, erect penises, rounded breasts, and marked buttocks proliferate. Wilinsky, the French illustrator said Crepax drew the best ass of any comic strip artist and certainly that part of O’s anatomy comes in for its full share of cruel treatment in Story of O.

The critic Ghera has pointed out, “The body of O, in addition to the brutalized level of the narrative fable, is freely manipulated in accordance with a scheme which is obsessively geometrical: the heroine is often on her knees or displayed systematically at an angle, a square or another angle; or otherwise here the image is broken up into different parts as if it were pieces of mosaic…” This mosaic is the “mirror in fragments” and Crepax breaks down the narrative into little boxes in which we see the sphincter or the vagina, or the open mouth of the heroine forming a perfect “o”. But here and there this rigid geometry is under threat of collapse, of being sucked into some threatening void which is about to open up in the background, amongst the clutter of opulent furnishings, drapes or architecture.

We are reminded that the progression from Valentina! (1965 – ) through Bianca (1968/71), Anita (1979), to ever more sophisticated Valentina, and eventually to Story of O (1973, 1974 & 1984/5), Emmanuelle (1978), Sade’s Justine (1979), and Sacher-Masoch’s Venus in Furs (1983) was inevitable. This “weaver of innocent plots” is indeed, as Frediani describes Crepax, “a hunter of butterflies”. Crepax points out, “From the point of view of eroticism it’s the atmosphere, the situation, which gives the scene its eroticism.” Valentina, Bianca, O are the victims of the most barbaric treatment always amidst splendid and baroque backgrounds. Pursued through labyrinthian perils, raped, whipped, and entangled in all manner of bizarre Heath-Robinson-like torture machines, they always emerge, however, Pheonix-like from their ordeals.

As Paolo Caneppele and Gunter Krena point out in their introduction to Venus in Furs /Bianca / Emmanuelle, ‘Ineffable as desire may be, it can nonetheless be represented’. Crepax leaves an indelible impression. Take a look at these long-awaited volumes from Taschen. These “innocent plots”, of butterflies pursued. You might either adore him or loathe him but without a doubt, there will never be another comic book artist quite like Guido Crepax. He has no imitators, no “Crepax tradition” – ‘My way of telling stories,’ maintains Crepax, ‘is so remote from tradition that young artists – rightly, I confess – choose other models. I have no desire to serve as a model. My universe is truly my own.’

Valentina Crepax Serie Tv

(spring 2000/ published in Skin Two no.33)

Valentina Crepax Morta

Guido Crepax (1933 – 2003)

Crepax Valentina Orologio

2020 Update: The publishers Fantagraphics Books have set out to publish in the English language, the complete works of Crepax, an amazing undertaking.